Overview

Kava is a shrub in the pepper family native to the South Pacific islands, and the name “kava” also refers to the mildly intoxicating drink made from its roots. The plant has heart-shaped green leaves and reaches a height of 2–3 meters when mature. Kava has been cultivated for at least 3,000 years by Austronesian and Polynesian cultures, who selectively bred it from a wild relative (Piper wichmannii). The traditional kava beverage is prepared by grinding or pounding the thick roots of the plant and mixing them with water to produce an earthy, opaque infusion with a distinctive pungent taste and a numbing effect on the mouth. It is consumed socially and ceremonially for its relaxant and psychoactive properties, which are often compared to those of alcohol but with some important differences.

When consumed, kava induces a state of calm relaxation, muscle looseness, and elevated mood or euphoria, typically without impairing mental clarity at moderate doses. Users often experience initial talkativeness and sociability, followed by tranquil contentment and eventually drowsiness or sleep, especially at higher doses. Because of these soothing effects, kava has gained significance not only in its indigenous contexts but also globally: it is used as a natural anxiolytic (anti-anxiety aid), a stress-relief drink at specialized “kava bars,” and an herbal supplement alternative to prescription sedatives. Importantly, kava is non-addictive and does not produce a physiological dependency or classic withdrawal syndrome. Public health organizations (including the WHO) consider moderate, traditional-style use of kava to pose an acceptably low level of health risk. However, concerns have been raised over improper use of concentrated extracts, which in rare cases have led to liver toxicity (see Safety & Cautions). Overall, kava holds a unique place as a neurobotanical substance – deeply rooted in the cultural and spiritual life of Pacific Islanders, yet also studied by modern science for its anxiolytic and sedative effects on the nervous system.

History & Cultural Context

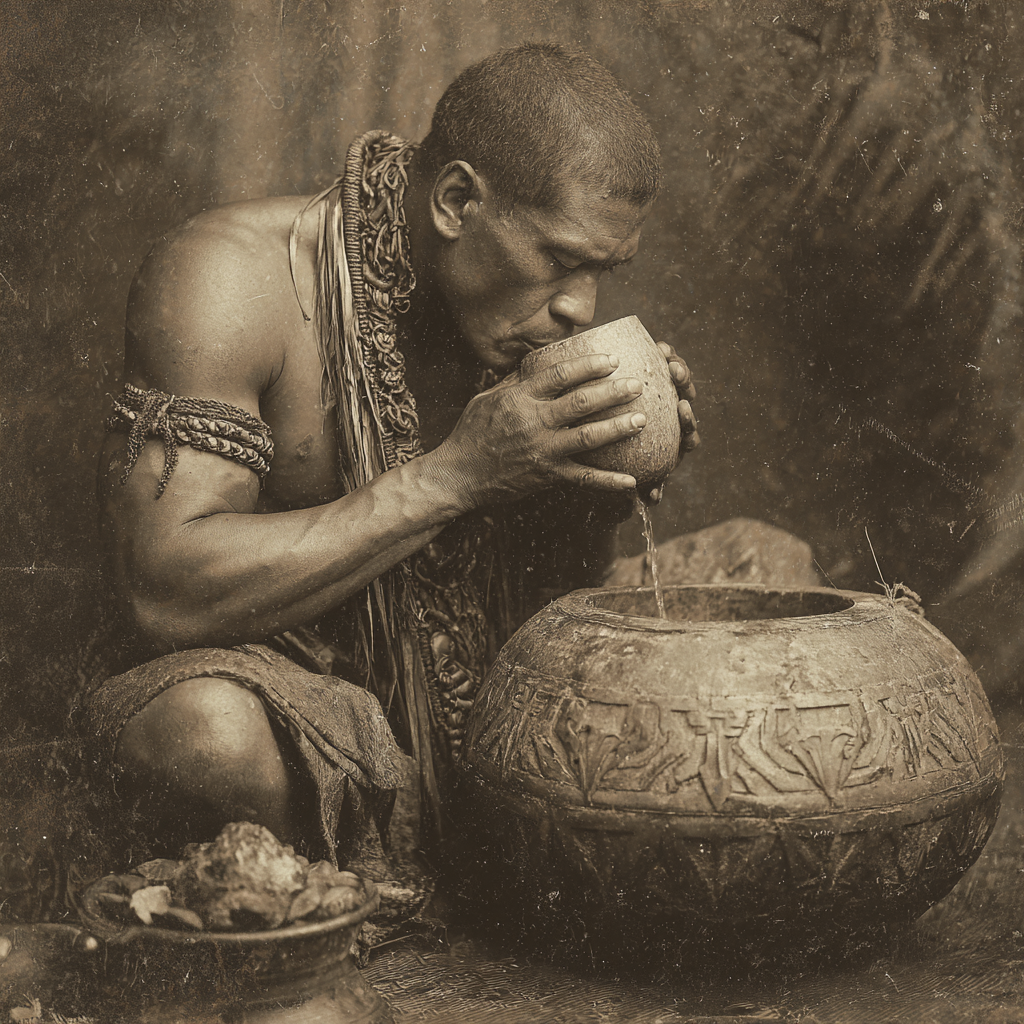

Fijian men performing a traditional kava (yaqona) ceremony, in which the pounded root is mixed with water in a wooden bowl (tanoa) and shared communally. Kava rituals hold great cultural and spiritual significance across many Pacific societies.

For centuries, kava has been central to the social and sacred life of Oceania. According to Polynesian oral histories, the origin of kava is infused with mythology and reverence. A famous Tongan legend tells of a poor couple who sacrificed their only daughter, Kava, to fulfill a visiting king’s request for food; from her gravesite sprouted two plants – one kava and one sugarcane – revealed by a tipsy mouse to have intoxicating properties. Ever since, kava in Tonga is considered a sacred gift – a bridge between the living and the ancestors – and the ceremonial kava drink is prepared to honor chiefs and connect with the spirit world, especially during coronations or other momentous occasions. Similar origin myths and rituals are found across the Pacific. In Samoa and Fiji, for example, kava (there called ʻava and yaqona respectively) is an emblem of hospitality and unity. A formal yaqona ceremony in Fiji will accompany important events – with participants seated in a circle, a facilitator mixing and serving the brew in coconut shell cups, and chants or claps offered in respect. These traditions reinforce social bonds: kava is used for medicinal, religious, political, and cultural purposes, and drinking sessions facilitate communal dialogue, storytelling, and peace-making. The nakamal (meeting house) in Vanuatu or the fale in Samoa, where kava is shared, serves as a space of goodwill and connection among communities.

Historically, kava consumption was likely spread by Austronesian voyagers. Botanists believe kava originated in northern Vanuatu and was spread eastward by the Lapita people into Polynesia about 3,000 years ago. It does not grow in colder climates, which is why, for instance, kava reached Hawaii (known there as ʻawa) but not New Zealand – the Māori instead ritualized a different but similarly named plant (kawakawa) in its place. Throughout Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia, kava drinks became imbued with status and spirituality. Some societies reserved kava for chiefs, priests, or special ceremonies, while others incorporated it into daily social life. European explorers in the 18th century, such as Captain James Cook, encountered kava and recorded its use as an “intoxicating pepper” beverage integral to island culture. However, in the 19th century, Christian missionaries often frowned upon kava, viewing the communal intoxication and pre-Christian spiritual connotations as sinful or unhygienic. In several islands, missionaries attempted to suppress kava drinking. Notably, the shift from using fresh roots to dried kava in some areas has been attributed to those colonial influences – drying and storing the root may have helped conceal or preserve kava usage when open consumption was discouraged.

Despite such pressures, kava traditions endured and have even spread beyond their indigenous context in recent decades. Today, Pacific Island nations like Vanuatu, Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa not only continue their age-old ceremonies but also export kava as a cash crop. By the late 20th century, kava was introduced to Western countries as an herbal anxiolytic and recreational beverage. “Kava bars” – lounges where patrons drink bowlfuls of kava instead of alcohol – have appeared in many U.S. cities, providing an alcohol-free social alternative. By the 2010s, there were over a hundred kava bars in the US and Europe, bringing a modern revival of the communal kava experience. The growing global interest in kava has also led to conversations about cultural respect and sustainability. Pacific Island communities and scientists emphasize the importance of noble kava cultivars and traditional preparation methods to ensure both safety and authenticity in kava’s new markets. In essence, kava’s cultural story is one of resilience: from ancient myth and ritual, through colonial-era challenges, to a contemporary resurgence as a valued plant ally for stress and social relaxation worldwide.

Chemistry & Pharmacology

Kava’s psychoactive effects are primarily attributed to a group of compounds known as kavalactones (sometimes called kava pyrones). The kava root contains at least 15 biologically active kavalactones, of which six major ones account for roughly 90–95% of the plant’s pharmacological activity. These major kavalactones are kavain, dihydrokavain, methysticin, dihydromethysticin, yangonin, and desmethoxyyangonin. Each kavalactone has a slightly different profile of effects, and the chemotype (relative proportions) can vary by kava cultivar. The general chemical structure of kavalactones is a substituted α-pyrone; they are lipophilic molecules, which helps them cross the blood–brain barrier relatively quickly. In addition to kavalactones, minor constituents of kava include flavokavains (chalcone compounds) and a trace alkaloid called pipermethystine. Notably, pipermethystine is found in the leaves and stem peelings of the kava plant and is considered potentially toxic; traditional preparations use only the root/rhizome, thereby avoiding this alkaloid.

Pharmacologically, kava is a central nervous system depressant with a complex, multi-receptor mechanism of action. Unlike a single-target drug, kavalactones modulate several neural pathways in concert:

- GABAergic action: Kavalactones (especially kavain, dihydrokavain, methysticin, dihydromethysticin, and yangonin) potentiate GABA<sub>A</sub> receptor activityen.wikipedia.org. This is analogous to how benzodiazepines produce calming effects, though kavalactones bind at distinct sites on the receptor (they do not bind to the classical benzodiazepine site)en.wikipedia.org. The net effect is enhanced GABAergic inhibition, contributing to anxiolytic (anti-anxiety), sedative, and muscle-relaxant properties.

- Monoamine modulation: Kavain and methysticin inhibit the reuptake of norepinephrine, and possibly dopamine in some brain regions, leading to mild elevation of those neurotransmitters in the synapseen.wikipedia.org. This may explain kava’s ability to improve mood and sociability at lower doses (some users report mild euphoria or stimulation initially). Additionally, all six major kavalactones have been shown to reversibly inhibit MAO-B, an enzyme that breaks down neurotransmitters like dopamineen.wikipedia.org. MAO-B inhibition could further contribute to dopamine availability and neuroprotective effects, though at dietary doses this effect is moderate.

- Cannabinoid and other receptors: Yangonin, one of the kavalactones, has appreciable affinity for the CB1 cannabinoid receptor (the primary psychoactive target of THC)en.wikipedia.org. While kava doesn’t cause cannabis-like effects, yangonin’s CB1 activity might add to kava’s overall relaxing and mood-elevating profile. Some studies also suggest kavalactones may interact weakly with opioid receptors or other sites, but these are not fully characterized. (Interestingly, leaf extracts of kava showed some binding to dopamine D2, opioid, and histamine receptors in vitro, though such compounds are largely absent from root preparationsen.wikipedia.org.)

- Ion channel effects: Kavalactones (particularly kavain and methysticin) block voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels in neuronal membranesen.wikipedia.org. This local anesthetic action is immediately evident when one drinks kava—the tongue and lips go numb due to peripheral nerve signal blockadeen.wikipedia.org. In the CNS, mild blockade of Na<sup>+</sup>/Ca<sup>2+</sup> channels can dampen overall neuron excitability, contributing to muscle relaxation and anticonvulsive properties. Kavain’s action on ion channels is sometimes likened to a mild topical anesthetic or a muscle relaxant effect.

Through these diverse mechanisms, kava produces an overall sedative, anxiolytic, and motor-relaxant pharmacological profile, without a significant depressive effect on respiration at normal doses (unlike opiates or barbiturates). It is important to note that the exact molecular targets of kava are not completely understood and are an area of ongoing researchen.wikipedia.org. The synergy of multiple kavalactones likely underpins the nuanced subjective effects.

In terms of pharmacokinetics, kavalactones are relatively rapidly absorbed when taken as a beverage on an empty stomach. Users typically begin to feel effects within 15–30 minutes. Animal studies indicate kavain has an oral bioavailability around 50% and is well distributed, primarily acting on brain regions such as the limbic system, amygdala, and reticular formation that govern emotion and arousalen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Kavalactones are extensively metabolized in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes (especially CYP3A4 and others), followed by phase II conjugation (sulfation, glucuronidation, and glutathione conjugation)en.wikipedia.org. The metabolism produces various metabolites (e.g. 4′-OH-kavain conjugates), which are excreted in urine. The elimination half-life of kavalactones in humans is not definitively established, but one clinical fact sheet suggests a serum half-life of around 9 hours for an average kava extract dosehealth.nsw.gov.au. In rats, over 90% of a kavain dose was eliminated within 72 hours via urine and feces, with no evidence of bioaccumulationen.wikipedia.org. This suggests that kavalactones do not persist long-term in tissues and that frequent high-dose use is required to build up significant plasma levels. A point of note is that certain kavalactones (and their metabolites) can transiently inhibit some CYP450 enzymes, which has implications for drug interactions (see Safety & Cautions).

Finally, it’s worth mentioning the distinction between “noble” vs. “non-noble” kava cultivars from a chemical perspective. Noble kava varieties (traditionally grown for consumption in places like Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Hawaii, etc.) have a chemotype yielding desirable effects – usually higher in kavain and other uplifting kavalactones, with lower content of potentially nauseating or toxic components like flavokavains. Non-noble kavas, such as certain strains in Vanuatu nicknamed “tudei” (two-day) kava, have a different kavalactone profile (often more dihydromethysticin and flavokavains) that can cause heavier sedation, a hangover-like malaise lasting into the next day, or more risk of nauseaen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Traditionally, Pacific islanders avoided regular use of such varieties. Modern analyses have suggested that some of the adverse liver reactions reported in Europe might have been related to non-noble kava or improper plant parts being used in commercial extractsen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. This underlines how chemistry and cultural knowledge intersect: the safest and most pleasant kava pharmacological profile comes from the cultivars and preparation methods refined by indigenous use over millennia.

Subjective Profile

Kava’s effects depend on dosage, preparation, and the specific cultivar, but there is a common progression of sensations that users report. In general, a moderate dose of kava produces calm, contented relaxation without impairing cognition or judgmenten.wikipedia.org. Many users describe a clear-headed tranquility – unlike alcohol, which can cloud mental function, kava tends to ease anxiety and muscle tension while leaving one able to think and converse normallyen.wikipedia.org. The experience often begins with a distinct numbing and tingling in the mouth and throat as the kava drink is held and swallowed; this local anesthetic effect, caused by kavalactones, is stronger than that of benzocaine and can last several minutes on the tongueen.wikipedia.org. Shortly after, within 15–20 minutes, an initial uplift in mood and sociability may emerge. In Pacific cultures it’s noted that small amounts of kava can have a mild stimulant or clarifying effect – drinkers become talkative, friendly, and feel their “cares melt away” while remaining alerten.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. This phase is sometimes accompanied by subtle euphoria or a sense of well-being and mental clarity.

As time passes (30 minutes to an hour in), muscle relaxation and heavier tranquilization set in. The body may feel loose or slightly heavy, and coordination can become sluggish (high doses of kava can cause a distinctive shuffling gait known colloquially as “kava walk” due to mild ataxia). Anxiolysis (anti-anxiety effect) is prominent – kava reliably reduces feelings of worry and stress, which is why it’s been used traditionally to settle disputes and in modern times to self-treat anxietypubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.goven.wikipedia.org. Cognitive effects are generally characterized by preservation of clear thinking or even heightened introspective clarity, especially at moderate dosesen.wikipedia.org. People often report that while their body feels calm or pleasantly sedated, their mind remains lucid and aware (in contrast to alcohol’s stupefying effect). At higher doses, however, kava can cause mental sluggishness, sleepiness, and a dreamlike state – heavy consumption leads to strong sedation and a deep, restful sleep.

A well-prepared kava session often culminates in drowsiness. About 1–2 hours after consumption, many users experience a pronounced sleepiness that can facilitate easy drifting into sleep. Ethnographic records from the 19th century praised kava for “relax[ing] the body after strenuous efforts, clarif[ying] the mind and sharpen[ing] the mental faculties” when taken in moderate amountsen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org, and noted that a potent dose could induce slumber “without any mental after-effects” – indeed kava drinkers typically awaken without a hangover or cognitive fog, unlike with alcoholwikidoc.org. Some users even report vivid dreams or an increase in REM sleep after heavy kava drinking (this varies; kava’s impact on sleep architecture isn’t fully consistent, but anecdotal accounts of colorful dreams existwikidoc.org).

Physically, aside from muscle-relaxation, kava can cause slight numbing analgesia (helping with minor aches), pupil dilation and bloodshot eyes at high doses (a benign effect, but characteristic of heavy kava use)betterhealth.vic.gov.au, and in some cases nausea if a large volume of the bitter liquid is consumed quickly or if the particular batch is high in heavy lactones. Unlike stimulants, kava tends to suppress appetite a bit – regular kava drinkers often note reduced hunger following a kava sessionbetterhealth.vic.gov.au. Kava does not typically produce intense euphoria or drastic sensory alteration; it’s more of a subtle emotional and physical calming. There is no hallucination or loss of touch with reality (in fact, traditional users consider being “drunk” on kava as a time for thoughtful conversation or listening to stories, given the clarity of mind). Motor reflexes and judgment are affected enough that one should not drive or operate machinery under kava’s influence (reaction time is slowed). At the highest extreme of dosing – usually only achieved in ceremonial or abuse contexts – kava can cause temporary extreme sedation, inability to walk, and even a kind of waking dream state. Islander terms like “kava stupor” describe when someone has consumed so much (often of a strong cultivar) that they must lie down, limbs uncoordinated; in historical records, very large doses even led to reports of brief limb paralysis or deafnesshealth.nsw.gov.au, but these effects are transient and occur far beyond normal social use levels.

Notably, kava is not habit-forming in the way that many anxiolytics or alcohol are. People do not develop strong cravings for it, and there is little to no withdrawal if one stops using kava, even after long periodsen.wikipedia.orgbetterhealth.vic.gov.au. Tolerance can build with repeated use (the calming effects may become less pronounced unless dose is increased), but there is also anecdotally the “reverse tolerance” phenomenon where new users might feel nothing the first few sessions until their body adapts to kava. In terms of dose-dependent differences, one can summarize: low doses (e.g. a single shell or ~150 mg kavalactones) – mildly stimulating, mood brightening, social and anxiolytic effects; moderate doses (~300 mg kavalactones) – pronounced relaxation, stress relief, muscle looseness, contentment, and ready sleepiness; high doses (≥500–600+ mg kavalactones) – strong sedation, possible motor impairment (wobbly legs), deep dreamless sleep, and potential next-day lethargy or slight coordination issues (the “two-day” effect)health.nsw.gov.auhealth.nsw.gov.au. Throughout these stages, kava’s lack of hangover or significant after-effect is often appreciated – users generally awake feeling normal or even refreshed, assuming hydration and nutrition were maintained (heavy kava can dehydrate or dull appetite temporarily).

Preparation & Forms

Dried Kava root powder from Vanuatu, ready to be mixed with water. Traditionally, kava is prepared by grinding or chewing the root and extracting it into cold water; the resulting brew is strained and consumed fresh.

Traditional Preparation: In the classical method still used in Pacific villages, kava roots (either fresh or sun-dried) are pounded, ground, or chewed into a pulp, then soaked and kneaded in cool water to leach out the active componentsen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. The liquid is often prepared in a large wooden communal bowl. The fibrous root material is typically contained in a porous cloth or sack and wrung or squeezed repeatedly in the water, which gradually turns cloudy (opaque muddy gray or brownish) as the starches and kavalactones emulsifyen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. After several minutes of maceration, the plant fibers are wrung out and discarded, and the kava brew is ready to drink – traditionally served in coconut shell cups or other shallow bowls. Among some groups (notably in parts of Vanuatu), an older method was to chew small bits of fresh kava root and spit the juice into a bowl – the enzymes in saliva and the fine particle size from chewing were said to produce a particularly potent brew, though this practice is less common today except in very remote areasen.wikipedia.org. In any case, freshness matters: fresh green kava root yields a more aromatic and strong drink than equally potent dried root, due to volatile compounds that are lost upon dryingen.wikipedia.org. In Vanuatu, where kava culture is especially strong, people prefer to use fresh-picked roots at dusk each day. In Fiji and other places where fresh root may be scarce, dried and powdered root (“waka” grade, usually the lateral roots) is used – often about 1–2 tablespoons of fine powder per cup of water, left to steep (or actively squeezed in a cloth) for 10–30 minutesen.wikipedia.org. No heat is used, as boiling can degrade kavalactones; kava is a cold infusion.

The appearance and taste of traditional kava brew are distinctive. The liquid is a thick, earthy, and aromatic suspension – often described as looking like muddy water or thin chocolate milk. It has a strong bitter, peppery, and astringent taste, often causing a slight throat catch or cough in newcomers. Traditionally no flavoring is added (islanders simply “chase” it with fruit or tea if needed), since kava is valued for its purity of taste and effecten.wikipedia.org. Custom dictates that kava is to be consumed immediately after preparation, in a solemn or respectful manner (for example, clapping once and saying “Bula!” in Fiji before downing the shell). It’s usually consumed in rounds: a shell is filled and passed to each participant in turn. Because kava can unsettle an empty stomach, it’s common in some places to serve a snack or hot tea/meal after kava sessions – this also symbolically “closes” the kava ceremony and helps ground the participants after the mild intoxicating effectsen.wikipedia.org.

Modern Forms: Outside of the South Pacific, kava is available in various commercial preparations. The most common is dried kava root powder, sold by the pound or kilogram – users can prepare this much like traditionally, by mixing in water. To make it easier, specialized strainer bags (much like mesh tea bags) are used to contain the powder while kneading it in a bowl of water. Pre-packaged instant kava (dehydrated kava juice) and kava concentrates are also on the market; these can be stirred into liquid without needing straining. Additionally, kava extracts are sold in capsules, tablets, or tinctures as herbal supplements. Such extracts are often standardized to a certain kavalactone content (e.g. a capsule might contain 100 mg kavalactones). They offer convenience and no taste, though some traditionalists argue the effects are “hollow” compared to the whole brew. Extracts may use solvents like ethanol or CO<sub>2</sub> in manufacturing. It’s worth noting that around the early 2000s, some kava supplements were made with acetone or ethanol extracts of leaves/stems – practices now largely abandoned due to safety concerns. Reputable vendors today stick to root-only, water-based or food-grade solvent extracts and often specify if the kava is a noble cultivar.

Kava is also served in kava bars as a drink that approximates the traditional preparation. These establishments in Western countries usually mix a strong batch of kava each day and serve it in coconut shells or cups, sometimes alongside mixers or chasers like pineapple or juice to cut the bitter taste. The forms of kava one can encounter, therefore, range from a bowl of muddy traditional grog, to a brown capsule of dried extract, to even new innovations like kava chocolates or beverages blended with kava. Regardless of form, the key is the kavalactone content. A traditional shell in Fiji might contain ~150–300 mg of kavalactonesen.wikipedia.org. By comparison, one capsule of a kava supplement might have 50–100 mg. Preparation affects potency: a finely pounded or micronized powder yields more active compound in the drink than coarse chips. Likewise, “washed” kava (making a second batch from used root) will be weaker than the first extraction.

One should be cautious with non-traditional preparations. For instance, alcohol-based kava tinctures can feel more pharmacologically forceful and may stress the liver more than a water brew due to different kavalactone extraction profilesen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Some users adhere to an informal “rule” of consuming kava only in its traditional water-based form for safety. Indeed, international regulators and Pacific Island experts have recommended that only water or coconut-water extracts of root be used, not pills or teas made with other plant parts or strong solventsen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Finally, proper dosage and moderation in preparation is emphasized. A common guideline is to start with 1–2 shells of brew (or equivalent ~10 g root) and wait 15–20 minutes, rather than chugging too much at once. Kava’s effects can sneak up slowly, and over-preparing (using excessive root per volume) can lead to unpleasant nausea or over-sedation.

Safety & Cautions

Kava is considered safe in moderation and has been used for generations without evidence of addictive potential or major long-term health damage in its native contexten.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. However, certain risks and precautions have been identified, particularly when kava is used heavily, improperly, or in combination with other substances. Key safety considerations include:

- Liver Toxicity: The most prominent concern with kava is the potential for hepatotoxicity (liver injury). In the early 2000s, over 30 cases of serious liver damage (including hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver failure) were reported in people using kava extracts in Europe and the US, some requiring liver transplantsen.wikipedia.org. This led to bans or restrictions on kava products in several countries at the time. The evidence on kava’s liver effects is mixed and controversial. On one hand, epidemiological and traditional use data suggest that water-based kava consumed moderately (e.g. ≤250 mg kavalactones per day) has no significant hepatotoxic effecten.wikipedia.org. Many Pacific Islanders consume kava almost daily and do not exhibit liver disease directly attributable to it. On the other hand, idiosyncratic reactions have occurred: genetically susceptible individuals or those mixing kava with other liver-stressful agents might metabolize kavalactones in a way that produces toxicityen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Researchers have proposed several possible causes for the liver cases: use of wrong plant parts (leaves/stems with pipermethystine) in some supplement preparations, solvent-extracted concentrates that lack the balancing glutathione and other protective constituents of the traditional drinken.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org, drug interactions (kava can inhibit certain liver enzymes, potentially causing other medications to build up), or pre-existing liver conditions in the affected individualsen.wikipedia.org. Currently, most regulatory agencies urge caution but do not outright ban kava. For example, the U.S. FDA issued a consumer advisory in 2002 about potential liver risk and suggests those with liver disease or taking liver-active drugs avoid kavaen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. In 2020 the FDA also ruled that kava is not “Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS)” for use as an ingredient in mainstream foodsen.wikipedia.org (thus it remains a supplement, not to be added to beverages sold as food). Practical advice: Do not take high-dose kava every day for extended periods, avoid combining it with alcohol or acetaminophen (which also tax the liver), and watch for any signs of liver trouble (dark urine, jaundice, abdominal pain). If one sticks to traditional usage levels, the risk appears very low – a 2016 WHO review concluded that traditional kava beverage consumption has an acceptably low health risken.wikipedia.org.

- Skin changes (Kava Dermopathy): Heavy, chronic use of kava (usually over several months of near-daily high intake) can lead to a reversible skin condition known as kava dermopathy (called kanikani in Fijian)en.wikipedia.org. This presents as dry, scaly, flaky skin with a yellowish discoloration, typically starting on the palms, soles, and across the backen.wikipedia.org. It somewhat resembles ichthyosis (fish-scale skin). Kava dermopathy is benign and thought to result from interference with cholesterol metabolism or fat-soluble vitamin absorption (kava may deplete certain nutrients when overused)en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. The first sign is usually peeling of the skin; interestingly, some Pacific Islanders historically regarded this as a sort of “detox” and would deliberately drink a lot of kava to peel a layer of skin – though from a health standpoint, that’s not recommendeden.wikipedia.org. The good news: kava dermopathy resolves on its own once kava intake is reduced or stopped, usually within a few weeks the skin returns to normalen.wikipedia.org. It is not an allergic reaction per se (true allergy to kava is rare, though isolated cases of rash or facial puffiness have been noted)en.wikipedia.org.

- Other Long-Term or Heavy-Use Effects: Habitual heavy kava drinking (e.g. the equivalent of 20 or more shells per day, which is well above medicinal use) has been associated with general health impacts such as weight loss and malnutrition (partly because kava can suppress appetite and heavy users might substitute kava for meals)en.wikipedia.org, apathetic or depressive mood in some individuals (sometimes called “kava laziness”), mild anemia or blood cell changes, and elevations in liver enzymes (even without failure)en.wikipedia.orgbetterhealth.vic.gov.au. Some reports mention shortness of breath or reduced pulmonary function in extreme users, possibly from muscle relaxation effectsen.wikipedia.org. There are also anecdotal reports of red eyes (from pupil dilation and slight blood vessel dilation) and decreased libido or impotence in very heavy usehealth.nsw.gov.au – earning kava the nickname “devil’s weed” among some missionaries who observed a loss of sexual drive in chronic users. Most of these effects are reversible and not backed by robust clinical research – they tend to occur in contexts of abuse (such as in parts of Papua New Guinea and northern Australia where kava was sometimes misused in lieu of alcohol).

- Interactions with Other Substances: Caution is absolutely advised if combining kava with any other psychoactive or sedative substance. Kava’s depressant effects are additive with alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, opioids, and even antihistamines or muscle relaxants. For example, studies showed that drinking alcohol on kava leads to significantly more impairment than the same amount of alcohol alone. There was a case report of a near comatose state in a person who took kava extract together with the benzodiazepine alprazolam (Xanax). Both kava and benzos act on GABA, so this combination can be dangerous. Kava should also not be combined with antipsychotic medications or sleeping pills, as it could unpredictably potentiate their effects. Additionally, kava’s inhibition of CYP enzymes means it might slow the metabolism of certain drugs – for instance, levodopa (for Parkinson’s disease) when taken with kava led to increased “on-off” fluctuations in motor control, presumably by affecting drug levels. It’s wise to avoid kava if you’re on any medication unless a healthcare provider confirms no interaction. Furthermore, kava and herbal supplements that affect the liver (like high-dose valerian or certain Chinese herbs) might collectively strain liver function.

- Populations and Situations to Avoid Kava: Due to the above, pregnant or breastfeeding women are advised not to use kava – its safety is unproven and there’s a possibility of affecting the baby (plus the cultural norm in many islands is that only men drink kava in ceremonial settings, though this is changing). Individuals with liver disease or a history of alcoholism should avoid kava, since their livers may be more vulnerableen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Children and adolescents should not be given kava. And one should never combine kava with tasks requiring full alertness (driving, operating machinery) – kava can slow reaction time, cause eye focus issues, and induce relaxation unsuitable for such activitieshealth.nsw.gov.au.

- Quality and Adulteration: Choose high-quality, root-only kava products. As mentioned, some problems arose when unscrupulous suppliers included stems or leaves in powdered kava, or sold non-noble cultivars that were cheaper but harsher. Countries like Vanuatu have regulations now prohibiting export of non-noble kava and requiring that only roots are useden.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. It’s wise to source kava from reputable vendors that lab test for kavalactone content and absence of contaminants (like molds or adulterants). Kava should also be stored properly (cool, dark place) to prevent spoilage.

- Regulatory Status: In the United States, kava is legal and sold as a dietary supplement (not FDA-approved as a prescription drug)en.wikipedia.org. The FDA monitors adverse event reports and has issued warnings but has not banned it. Consumers are advised by the FDA to consult a doctor if they have liver issues and to discontinue kava if any liver-related symptoms appearen.wikipedia.org. In Europe, kava’s status has evolved: it was banned or restricted in many countries around 2002 due to the liver cases. Germany, which had led the ban, overturned the prohibition in 2014 after court challenges – now kava oral medicines are available by prescription in Germany with liver warning labelsen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Other countries like the UK still prohibit sale of kava as a consumable (one cannot sell kava for human use in the UK, though personal possession or use isn’t criminal)en.wikipedia.org. Poland had an outright ban that was lifted in 2018 (now legal to possess, but not to sell as food)en.wikipedia.org. Australia allows kava with limits: travelers can bring up to 4 kg, and it’s regulated as a controlled substance in some territories (Northern Territory limits possession)en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Notably, Australia’s TGA recommends no more than 250 mg kavalactones in 24 hours as a safety guidelineen.wikipedia.org. In the South Pacific producer countries, kava is of course legal and culturally protected, though they have their own quality controls for export. As of 2025, there is ongoing research to conclusively determine kava’s safety profile – for example, clinical trials are examining kava as a potential treatment for generalized anxiety disorder, with some promising results but also careful monitoring of liver enzymesen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

In summary, kava can be used safely when it’s high-quality, consumed in traditional-style preparations at moderate doses, and not mixed with other drugs. The primary risks – rare liver issues and certain reversible side effects – are generally avoidable with informed, responsible use. Always listen to one’s body: if signs of toxicity or intolerance appear, discontinuing kava is prudent. And as kava enthusiasts say, “Drink kava respectfully, and it will bless you with its calm.”

References

- Lebot, V., Merlin, M., & Lindstrom, L. (1997). Kava: The Pacific Elixir. Inner Traditions/Bear & Co. – Comprehensive ethnobotanical reference on kava’s history, cultural use, and chemistryen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

- Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organization (2016). Kava: A review of the safety of traditional and recreational beverage consumptionen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org – Joint WHO report detailing kava’s pharmacology, toxicity data, and risk assessment for traditional use.

- Sarris, J., et al. (2013). “Kava for Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A 6-Week Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial.” Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 33(5): 643-648. – Clinical trial suggesting efficacy of aqueous kava extract in anxiety treatment with no serious adverse effects (monitored under medical supervision).

- Showman, A.F. et al. (2015). “Contemporary Pacific and Western perspectives on ‘awa (Piper methysticum) toxicology.” Fitoterapia 100: 56–67en.wikipedia.org. – Scholarly review comparing traditional kava usage safety to Western cases, discussing possible reasons for hepatotoxicity reports.

- Olsen, L.R., Grillo, M.P., & Skonberg, C. (2011). “Constituents in kava extracts potentially involved in hepatotoxicity: a review.” Chemical Research in Toxicology 24(7): 992–1002en.wikipedia.org. – Investigates which kava constituents (e.g. flavokavains) or metabolites might contribute to liver injury, concluding that proper cultivar and extraction choice is critical for safety.

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH, NIH) – Kava Fact Sheet (2020)en.wikipedia.org. – U.S. health authority summary noting kava’s uses for anxiety and the associated liver injury advisories, legal status, and need for medical guidance.

- NSW Health Department (2022). Kava (Kavalactones) Fact Sheethealth.nsw.gov.auhealth.nsw.gov.au. – Contains pharmacokinetic info (peak levels, half-life), dose ranges, and outlines acute vs chronic effects of kava, used as a clinical reference in Australia.

- Wikipedia – Kava (accessed 2025)en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. – Encyclopedia entry providing an overview of kava’s names, traditional preparation, effects, and regulation (with extensive citations, some of which are reflected above).

- Better Health Channel – Kava (Victorian Govt., updated 2021)betterhealth.vic.gov.aubetterhealth.vic.gov.au. – Public health fact-sheet listing kava’s short-term effects, long-term problems from heavy use, and precautions (aligns with Australian law and medical consensus).

- Bilia, A.R., et al. (2017). “Safety and efficacy of kava (Piper methysticum) extracts in the treatment of anxiety disorders.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 198: 331-343. – A review of clinical studies on kava’s anxiolytic effects and safety, which generally supports short-term use for mild anxiety and discusses the liver issue debate.